THE ANTHROPOGENIC AMAZON

By William I. Woods*

<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<Click aquí para leer el artículo en español>

Many now view the Amazonian environment as a social construction and not as a culturally defining element. This perspective is a vision that goes beyond the dichotomy between human societies and nature; the human being is not considered a passive agent who simply reacts to stimuli. This shift in focus presents humans as agents who transform the landscape through the use and manipulation of resources and takes into consideration the inventive character of the human being. This perspective in Amazonia has put forward the genesis of fertile anthropogenic soils as the mark of cultural changes associated with intensive environmental management, including agriculture. The debate on the human articulation with the environment is ongoing, and the implications for pre-Colonial population numbers in Amazonia are considerable. This process of human manipulation and betterment of soils both intentional and unintentional is not restricted to Amazonia, but has been and is found throughout the world with both agricultural and non-agricultural populations and anthrosols are the result. Efforts are now being made by an interdisciplinary, international group of scholars to study the past, present, and future of soil manipulation and nutrient recycling.

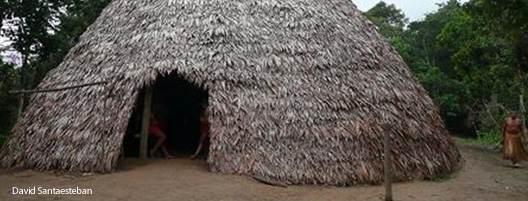

Past and present Amazonian Amerindian groups have typically been considered to be small, autonomous, non-sedentary, non-stratified polities, usually with single settlement units led by a headman of transitory, situational leadership. Such groups have been seen as dependent on extensive, rather than intensive horticulture, with both soil infertility and rare, dispersed protein contributing to the “counterfeit paradise” quality of their environment. While this model pertains to virtually all modern Amerindian groups in lowland Amazonia, it explains little of the regional archaeological record. Evidence of elaborate craft traditions, long-distance trade networks, large settlements, mound building, extensive raised field systems and other earthworks, and enormous cumulative areas of anthropogenically enriched soils were all known for prehistoric Amazonia well before this “standard model” became standard. Yet, this evidence was ignored, explained away as some form of cultural intrusion from the Andes or limited to a few “ecologically rich” environments such as the so-called “whitewater” settings where fertile floodplains enabled extraordinary forms of cultural elaboration.

The past few decades of research have more than called into question this monolithic view of regional Amerindians. Evidence from Marajó Island, the Llanos de Mojos, and the Tapajós, Negro, Solimões, Xingu, and Purus drainages, as well as many other less well known locations in Colombia for instance, has provided us with an interpretation rather different than the “standard model.” At least by, but probably well before, the advent of the Christian era, successful articulations with and modifications of the environment including true sedentism based upon intensive agroforestry and farming involving a host of domesticates was present in many Amazonian settings, and numerous groups were moving toward full blown sociopolitical complexity. During the next 1,500 years these trends became even more widespread regionally. Large and small settlements were not restricted to major riverine settings, but were also found near the headwaters streams well into the interior and together encompassed millions of inhabitants.

The forces unleashed by the arrival of Europeans and others brought collapse to this and virtually all Amerindian groups during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and those who survived only then came to resemble the characteristics of the “standard model” for the Tropical Forest Culture.

When discussing quality of life and population numbers, subsistence considerations become paramount; people consume food. It is becoming increasingly clear that Amazonian responses to problems of food production utilized an array of adaptations consisting of a multitude of varieties of cultigens and semidomesticates, agroforestry, focused manipulation of local ecologies, and large scale modification of soil conditions. Patches of exceptionally fertile, anthropogenic dark soils occur throughout lowland portions of the basin (Figure 1). These have been used to support numerous theories concerning pre-European settlement patterns, population densities, and cultural development. Heightened biotic activity and nutrient retaining capacity brought about by deposition of charcoal and organic material appear to be principally responsible for these soils’ remarkable persistence long after their cultural manipulation has ceased (Lehmann, et al. 2003; Glaser and Woods 2004; Woods, et al. 2009; Teixeira et al. 2010).

Why have these soils largely overlooked by researchers? The culprit is clearly the tyranny of scale. No maps of the Amazon Basin depict these soils; individual expanses rarely exceed more than a few square kilometers and usually encompass much less area. However, when taken together their cumulative expanse is tremendous. We must remember that if you don’t look for something you won’t find it and almost everywhere investigators have recently looked they have found dark earths. Reports from Brasil, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela,, all point to the widespread distribution and immense cumulative area of these anthropogenically enriched soils. If only 1% of the lowland portion of the Amazon Basin consists of dark earths that translates into approximately 60,000 square kilometers or 6 million hectares; an enormous amount of fertile soil. Did this huge productive capacity translate into the reality of production? Right now, the answer is “Yes, but to an unknown degree.” Even with such equivocation the i

mplications for population estimates and related environmental are tremendous.

So, we have a long period of human interaction with and manipulation of the Amazonian environment that by 1491 had led to a situation that would not by any measure be considered natural or pristine. What ultimately would have been the outcome of this experiment in domesticity? We don’t and will never know since, as with so much else in the Hemisphere, its trajectory was truncated in 1492 and we are left with the remnants of the feral garden.

One final, more general note is required. We must understand that the pre-European inhabitants of the Amazonia were human with the entirety of positive and negative consequences that such a stance entails. These people lived their lives striving to make their world better for themselves, their families, and future generations and in so doing accomplished variable degrees of success and failure.

Theirs, as ours, was a dynamic physical and cultural environment with complex interactions and it is the evidence of the resultant changes and their links to the process that we are just beginning to understand. Investigation of their lifeways and how they changed their environment and how these traditional practices can be understood and applied to modern settings involves interdisplinary efforts. While a focus on Amazonia is proposed, anthrosols are a worldwide phenomenon and applications of the Amazonian investigations will have productive implications for the future of agriculture throughout the world.

References

Glaser, Bruno, and William I. Woods, editors. 2004. Amazonian Dark Earths: Explorations in Space and Time. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 216 p.

Lehmann, Johannes, Dirse C. Kern, Bruno Glaser, and William I. Woods, editors. 2003.

Amazonian Dark Earths: Origin, Properties and Management. Kluwer Academic Publishers,

Dordrecht. 505 p.

Teixeira, Wenceslau G., Dirse C. Kern, Beáta E. Madari, Hedinaldo N. Lima, and William I. Woods, editors. 2010. As Terras Pretas de Índio da Amazônia: Sua Caracterização e Uso deste Conhecimento na Criação de Novas Áreas. Embrapa Amazônia Ocidental, Manaus. 421 p.

Woods, William I., Wenceslau G. Teixeira, Johannes Lehmann, Christoph Steiner, Antoinette WinklerPrins, and Lilian Rebellato, editors. 2009. Amazonian Dark Earths: Wim Sombroek’s Vision. Springer, Berlin. 502 p.

______________

*William I. Woods is a Professor of the Department of Geography in the University of Kansas. His research interests center on Abandoned Settlements, Anthropogenic Environmental Change, Cultural Landscapes, Soils and Sediments, Traditional Settlement-Subsistence Systems. He has extensive field experience in Mexico, Brazil, Belize, Belgium, Germany, and Italy; with lesser amounts of time in Argentina, Colombia, and Ireland. He presently a member of research teams working with anthropogenic soils and related environmental history and prehistory in the Brazilian Amazon, Belgium, and at the UNESCO World Heritage Cahokia Mounds Site in southwestern Illinois. Another current research topic concerns carbon sequestration in soils as a potential mitigating process for land degradation and atmospheric CO2 accumulation. An ancillary interest involves birds has an indicator of anthropogenic environmental change.

Contact: wwoods@ku.edu